GLD – The Central Bank Of The Bullion Banks

1 June 2012 50 Comments

The black curve (left scale) of the following chart shows the London pm gold fixing in U.S. dollars from 1 January 2006 to 30 April 2012. During the light-blue intervals which span about 35% of the entire period, the gold price increased at an annualized rate of 41.1%. During the remaining intervals, the price increased only at an annualized rate of 7.9%. The light-blue intervals are the result of a trading algorithm whose buy signals are indicated by the green dots and whose sell signals by the red dots.

In this article, we explain how the signals can be computed from the variations of the inventory of the SPDR Gold Shares exchange traded trust (NYSEArca:GLD). We explain why the inventory adjustments can hardly be caused by price arbitrage between the GLD share price and the loco London spot price alone. We rather claim that bullion banks finance their inventory by lending it or selling it to GLD investors and that bullion banks manage their physical reserves by accessing the physical gold inside GLD.

The fact that a certain type of inventory adjustments has predictive power, supports the idea that large inventory changes are the result of active reserve management. This provides us with a unique window into the flow of physical gold that is usually obscured by the dominance of paper gold trading. A similar, but somewhat less robust result is shown for the iShares Silver Trust (NYSEArca:SLV).

WARNING (April 2013): This article uses the term buy signal in a technical sense. It does not mean that you ought to buy anything without understanding what you are doing. Notably, the rapid price increases after the buy signals have been absent since the fourth quarter 2012. Now you might dismiss the trading algorithm as a statistical fluctuation. Alternatively, you can wonder whether something might have changed.

The idea of a trading strategy based on changes to the GLD inventory goes back to Lance Lewis’ GLD Puke Indicator. The term Central Bank Of the Bullion Banks was coined by FOFOA who wrote about the GLD Puke Indicator in Who Is Draining GLD. In that article, FOFOA expands on Randal Strauss’ idea that GLD redemptions indicate a preference for physical gold over paper gold (see his Gold Dips Towards $1360/oz … and Gold Nears 3-Months Low…).

Creation and Redemption of GLD Baskets

The method by which GLD grows or shrinks differs radically from the way in which conventional investment funds operate. If you want to invest in such a fund, you wire money to the manager. If you wish to withdraw money, you fax them a withdrawal notice. Depending on the contributions and withdrawals, the manager then either invests the contributed cash or sells investments in order to satisfy the requests for withdrawal.

GLD is managed differently. As of 29 May 2012, there exist about 421 million shares of the trust. Each share corresponds to roughly 0.097 ounces of gold. The trust therefore contains 40.84 million ounces of gold (1270 tonnes) that are worth $64.5bn at the London pm fixing price of $1579.50 per ounce.

The number of shares of the trust can be changed only in multiples of a basket (100000 shares) and only by the so-called Authorized Participants (APs). According to the prospectus of 26 April 2012, these are Barclays, Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, J.P. Morgan, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Newedge, RBC, Scotia, UBS and Virtu Financial. Each of these APs can

- Transfer the physical gold that corresponds to a basket of shares to the trustee. The trustee then creates a basket of new shares and transfers them to the AP in return (creation)

- Transfer a basket of shares to the trustee and receive the corresponding physical gold in return. The trustee then cancels the shares (redemption).

Note that all the gold held by the trust is allocated except for an adjustment term that is smaller than one 400oz London Good Delivery (LGD) bar.

Creation and Redemption Statistics

Before we consider why an AP might wish to create or redeem baskets, let us take a look at the statistics of these creations and redemptions. The following histogram shows the frequency of the daily inventory changes depending on their size in millions of ounces (creations are counted positive, redemptions negative). Days on which the inventory remained constant, are ignored. We have analyzed the period from 1 January 2006 to 30 April 2012. Recall that one basket consists of 100000 shares which presently represents 9700 ounces or 301.67kg of gold, worth about $15.3 million.

Distribution of daily GLD inventory changes in millions of ounces from 1 January 2006 to 30 April 2012

We see that the changes to the inventory are not exactly normally distributed. In addition to a skew towards small redemptions and larger creations, there are obvious fat tails on both sides. In the following, we are interested in these fat tails, i.e. in the excess number of large creations and large redemptions.

The Trading Strategy in Detail

For GLD, we are interested in creations and redemptions that exceed the threshold of 250000 ounces on a single day, i.e. about 25 baskets or 7.78 tonnes (presently worth $394 million). Note that this threshold essentially captures the fat tails of the distribution of inventory changes displayed above.

On the first day (1 January 2006), our strategy is not invested. At about 4.50pm New York time on every New York trading day, i.e. after the close, the current inventory of GLD is published. If the strategy is not invested and the inventory has decreased by 250000 ounces or more compared with the previous trading day, our strategy buys gold at the London pm fixing price on the following day. If the strategy is invested and on any New York trading day, the inventory has increased by 250000 ounces or more, our strategy sells the gold at the London pm fixing price on the following day. These buy and sell signals are indicated by the green and red dots in the chart at the beginning of this article. The blue curve (right scale) shows the total inventory of GLD in millions of ounces.

Recall that the original GLD Puke Indicator by Lance Lewis counts a decrease of the inventory by 1% or more as a buy signal. We prefer an absolute threshold (250000 ounces) rather than a relative one. This yields a more consistent performance of the strategy over the entire period from 2006 to 2012 and is also more plausible in view of our interpretation of the inventory changes as reserve management (details below). Note that GLD began trading on 18 November 2004, and we have omitted the first 13.5 months from the analysis.

Of course, nobody would actually trade according to this strategy, simply because even during the times at which the strategy is not invested, the gold price still increases at an annualized rate of 7.9%. The strategy merely serves to demonstrate that inventory changes do have some power of predicting the future gold price.

Price Arbitrage

Let us now consider why an Authorized Participant (AP) might wish to create or redeem baskets of GLD. We therefore need to understand how GLD is priced and which type of arbitrage might enforce this price.

Assume you know from the data sheet that one share of GLD corresponds to 0.097 ounces of gold and that the London spot price is $1579.50 per ounce. This yields a Net Asset Value (NAV) of $153.21 per share. Even if you do not know the price at which GLD is currently trading, you nevertheless know that one share of GLD is worth $153.21. So if you bid $153.21 per share (plus spread), you should be able to purchase your shares of GLD, simply because GLD contains physical gold loco London that you could equally well purchase directly for the spot price (plus spread).

If you bid less than $153.21, you cannot expect to receive any shares, simply because the seller would be foolish to sell at this price. If you bid more than $153.21, you would effectively hand a free lunch to the seller. In fact, if you did, your counterparty can indeed capture this free lunch by arbitrage.

Paper Gold Arbitrage

Suppose there is a buyer of GLD shares who acts foolishly and who drives up the price of GLD shares well beyond their NAV. Any arbitrageur can now go short GLD and long any other gold investment that follows the London spot price. This allows him to capture the arbitrage, i.e. to lock in a risk-free profit. This works because GLD will eventually trade at its NAV again, and the arbitrageur can unwind both positions at that point in time. We call this form of arbitrage paper gold arbitrage because the arbitrageur can go long unallocated gold in addition to short GLD while the physical gold inside GLD is not touched.

If for some reason, GLD trades at a discount to its NAV, the arbitrageur can go long GLD and short paper gold. Most likely, GLD will sometimes trade at a small premium to NAV and at other times at a small discount, and so the arbitrageur can easily unwind the paper gold arbitrage after a short period of time.

Let us stress that paper gold arbitrage should be largely unnecessary though, simply because every investor knows that the NAV is the price at which GLD ought to trade. Deviating from this price would be foolish, and so in most cases the threat of arbitrage ought to be sufficient in order to keep the market efficient while the actual arbitrage would not be necessary.

In the unlikely event that there is so much buying pressure that GLD consistently trades at a premium even though paper gold arbitrage is performed, the short GLD and long unallocated gold positions of the arbitrageur would keep growing. How can this be avoided?

Creation-Redemption Arbitrage

The answer is that if an AP performs such an arbitrage and his position of short GLD versus long unallocated gold has grown beyond the size of a basket, he can unwind the position at any time by having a basket created, i.e. he

- has a basket worth of his unallocated gold allocated,

- transfers the gold to the trustee,

- receives a basket of created shares,

- uses these shares in order to close his short position in GLD.

If GLD has traded at a discount for some time, and the AP has accumulated a position of long GLD versus short unallocated in order to lock in the arbitrage profit, he can unwind this position by redeeming a basket, i.e. he

- transfers a basket of shares to the trustee for redemption,

- receives a basket worth of allocated gold,

- uses this gold in order to close his short unallocated position.

Whereas paper gold arbitrage has very little transaction costs, the creation and redemption of baskets involves the reallocation of gold and possibly even physical movements of gold bars into another vault, and is therefore subject to higher transaction costs. Note that Warren James at Screwtape Files discovered a fax from HSBC, the custodian of GLD, that confirms the reallocation of about 760000 ounces (or 1907 LGD bars of about 400oz each) related to the redemption of 79 baskets by Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, and J.P. Morgan on 16 August 2011.

Due to the transaction costs, the APs will avoid the creation-redemption arbitrage as far as possible and perform it only if their paper gold arbitrage position gets way out of balance. Let us finally recall that every market participant knows the NAV and the spot price and therefore the fair price of a GLD share, and so even paper arbitrage should normally be unnecessary.

Then why do we see so many inventory adjustments? Is there a second reason for adjusting the inventory beyond the obvious price arbitrage?

Two Different Views on Inventory Changes

How can we better understand the creation and redemption of baskets? The arbitrage point of view was the following:

Some investor decides to buy a certain number of GLD shares, but he is not interested in other gold investments. If he is willing to pay a premium for these GLD shares if necessary, he will definitely get the desired number of shares. The price to pay is that an AP who acts as the arbitrageur, can pocket that premium as a profit for the service of creating the desired number of shares.

There is, however, a second point of view on the creation and redemption that is not centred around the GLD investor, but rather around the AP. Let us assume the AP decides to put a certain amount of gold into GLD. He therefore transfers the gold to the trustee, receives GLD shares in turn and sells these shares into the market. If GLD shares trade at a discount as the consequence, the rest of the market can act as the arbitrageur and, for example, slightly favour GLD over other gold investments, and thereby absorb all the newly created GLD shares.

So which one is it? Do the investors in GLD request a certain number of shares, and the AP delivers by performing the arbitrage and creating the shares? Or does the AP decide to place a certain amount of gold into GLD, and then the market absorbs these additional shares?

We suspect that at least those inventory adjustments that constitute the fat tails of the distribution, i.e. beyond the threshold of 250000 ounces per day, are in effect initiated by the AP rather than by the GLD investors.

If it were just the arbitrage in response to the investors, why would the trading strategy work? The only explanation would be that GLD investors represent the ‘dumb money’ (or ‘weak hands’) whereas all other gold investments represent the ‘smart money’ (‘strong hands’). In this scenario, GLD would lose a significant amount of inventory when the dumb money sells while the smart money buys, triggering a buy signal. Conversely, when the smart money sells and the dumb money buys, GLD would gain inventory which constitutes a sell signal.

The problem with this view is, however, that there is no reason to assume that GLD is held primarily by the weak hands whereas the other gold investments that are all tied to the London spot price, represent the strong hands. Both GLD and unallocated gold OTC or COMEX futures are held by sophisticated investors, endowment funds or hedge funds. Although many retail investors, i.e. typically weak hands, are in GLD, the same is true for other gold investments such as coins and retail bars, COMEX futures, and bank sponsored gold-related products that, in aggregate, all appear on the other side of the arbitrage, i.e. in the spot market outside of GLD.

The only consistent interpretation would be the following: The fact that the suggested trading strategy works, confirms that in aggregate GLD is dominated by weak hands whereas in aggregate all other gold investments are dominated by strong hands. This point of view is not plausible at all.

We therefore suspect that those inventory adjustments that are relevant to our trading strategy, i.e. those beyond 250000 ounces per day that form the fat tails, are rather initiated by the APs.

Inventory Financing and Reserve Management

Why would an AP decide to increase or decrease the inventory of GLD other than in order to capture some arbitrage profit? There are two plausible scenarios. In order to understand them, let us first note that all market makers except two (Mitsui and Société Générale) and all clearing members of the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) are presently APs of GLD.

Inventory Financing

Consider a company whose operation requires an expensive inventory. In order to stay in the realm of the gold market, this might be a large coin store, a refiner or mint, or even the market maker of a public exchange. The regular operation requires a considerable gold inventory, but this inventory ties up a lot of capital.

In order to reduce the capital requirement, our company has several options, for example,

- To take out an unsecured loan in order to finance the inventory. This is usually an expensive strategy.

- To Take out a loan for which the inventory serves as the collateral. Given that the inventory is gold bullion, the collateral is easy to liquidate, and so the interest expenses on such a loan should be a significantly lower than those on an unsecured loan.

- To swap the gold for dollars with a bullion bank, i.e. our company borrows dollars from the bank and at the same time lends gold to the bank, both for a fixed term. This is almost the same as taking out a loan that is secured by the gold. Since such swaps are typically limited to 400oz LGD bars, this method is suitable for the market maker, but not for the coin dealer or for the refiner.

- To give private investors an opportunity to own a part of the inventory. The pooled accounts offered by Kitco or by the Perth Mint are examples of this type of inventory financing. Our company can sell the title to gold that forms part of the inventory, to private investors and offer to buy it back from them. Such a pooled account is indeed backed by physical gold, but this is the physical gold that flows through our inventory anyway. Voila, somebody else owns our inventory, and our capital is no longer tied up in order to hold this very inventory.

The London bullion banks can use GLD in precisely the same fashion as the last one of the above examples. They typically have many flow positions that contribute to their inventory, for example, receiving gold that has been sold forward by a mining company and then selling this gold to a wealthy investor. As long as the bullion bank knows which part of their inventory corresponds to this flow and how long it is held for, they can just move this inventory into GLD where it is owned by private investors and no longer ties up any capital.

Even better, should the portion of the inventory corresponding to this flow decrease unexpectedly, they can even purchase a basket of GLD shares in the market, redeem them and recover the gold at any time. In this sense, GLD is even superior to the Kitco pooled account. Kitco can decrease their inventory only if some of the investors in their pooled account decide to sell. GLD offers the advantage that there is a liquid market for GLD shares from which the bullion bank can purchase additional shares at any time. The average daily trading volume of GLD is about 12 million shares which represents an inventory of 1.16 million ounces or 36.2 tonnes.

Reserve Management

A second use of GLD for the bullion bank besides the financing of a part of their inventory is reserve management. This plays a role for every institution that accepts bank deposits in ounces, that lends ounces and that holds only a fractional reserve of physical gold against this created credit. For example balance sheets, we refer to Bullion Banking with Alice and Bob.

The bullion bank can hold gold instruments in various forms, for example,

- physical gold in the vault,

- allocated balances with other institutions,

- shares of GLD,

- unallocated balances with other institutions,

- outstanding loans denominated in ounces,

- long OTC Forward or COMEX futures positions,

- and many others.

Only the first three of these are free of credit and counterparty risk and can therefore be considered as reserves. This is analogous to the reserves of an ordinary commercial bank that is in the business of lending dollars. The reserves of the commercial bank consist of cash in the vault and of reserve balances with the respective central bank.

Besides the credit risk, i.e. the risk that a counterparty fails to honour its obligations, any bullion bank that holds only a fractional reserve against their customers’ deposits, is exposed to liquidity risk. For example, customers might request allocation of their unallocated account balances. In this case, both a liability of the bank (the customers’ unallocated account balance) and an asset (a reserve of physical gold) disappear from the balance sheet. This is analogous to a customer withdrawing dollars in cash from a commercial bank or to a customer transferring out credit money from her account.

Since such a withdrawal involves a reduction of our bullion bank’s reserves, our reserve ratio deteriorates. We now have less reserves relative to the size of our balance sheet. This is where GLD comes in handy. We can easily replenish our reserves by

- selling unallocated gold or other instruments that involve credit or counterparty risk, and

- purchasing shares of GLD, and optionally

- redeeming these shares for physical gold.

In effect, on our balance sheet, we have replaced credit assets (paper gold) by reserve assets (GLD shares or physical gold).

Shortage of Reserves and Reduction of GLD Inventory

Although inventory financing may be one of the motivations for establishing GLD and for the APs to place additional gold in GLD, it is not the activity that correlates with the inventory changes on which our trading strategy is based. The reason is that our strategy is based on the creation and redemption of GLD baskets, but inventory financing occurs when a bullion bank sells existing shares of GLD to an investor.

Let us try to disentangle these steps. The bullion banks presumably hold a part of their reserve in the form of physical gold in their own vault and another part in the form of GLD shares. Whenever they acquire a larger amount of additional physical reserves, they probably place some of it into GLD and create new baskets of shares, but they do not necessarily sell these GLD shares to investors and even if they do, this need not happen at the same point in time.

Conversely, if a bullion bank faces a large allocation request and needs to replenish the physical gold in their vault, they can redeem baskets of GLD that they already own. In a true emergency in which a bullion bank runs out of reserves, they can even

- sell some paper gold, and

- purchase GLD shares with the proceeds, and optionally

- redeem these GLD shares in order to receive physical gold,

thereby replacing a credit asset (paper gold) with a reserve asset (GLD shares or physical gold).

Since our trading strategy uses only the instances in which shares of GLD are redeemed for physical gold, it is sensitive to the following two situations:

- The bullion bank has purchased shares of GLD in order to boost its reserves. In order to achieve a balance between their two forms of reserves, i.e. GLD and physical gold in the vault, they redeem some of these GLD shares.

- There has been a request for allocation by some investor who requires individual bars in the vault, and so GLD shares need to be redeemed in order to get to the bars.

We therefore expect that some changes to the inventory of GLD are related to the reserve management of the bullion banks. Excess reserves lead to a growing inventory of GLD whereas a shortage of reserves results in a reduction of inventory. If this picture is correct, we should find independent evidence that reductions of GLD inventory correlate with a shortage of reserves. There is indeed anecdotal evidence for such a correlation.

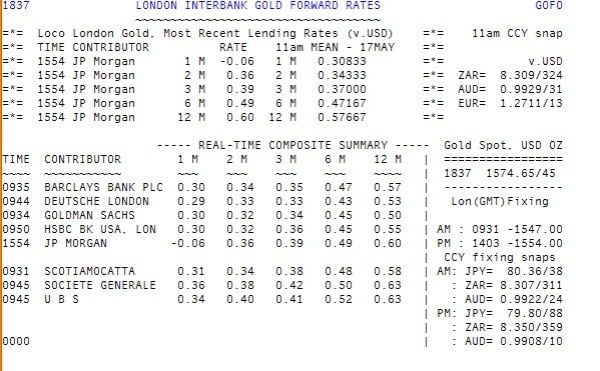

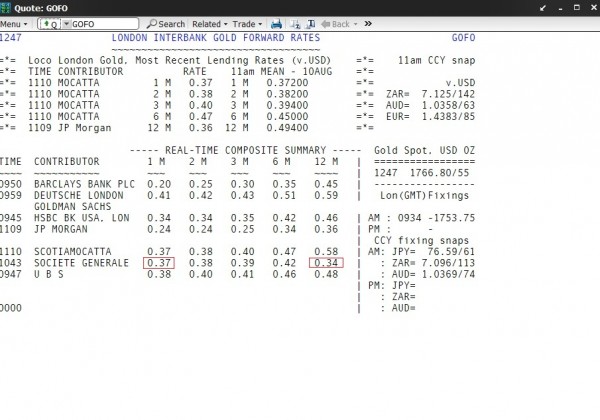

One of the largest recent reductions in GLD inventory occurred on 22 May 2012 with a net redemption of 563024 ounces, i.e. 58 baskets or about 17.5 tonnes. This event coincides up to one week with a negative one-month GOFO quoted by J.P. Morgan on 16 May 2012 as reported by Izabella Kaminska. This indicates that J.P. Morgan was presumably willing to pay a premium in order to swap dollars for gold, i.e. they were willing to buy at spot and sell a one-month forward at a discount.

Robert LeRoy Parker spotted another example. Some of the largest reductions in GLD inventory occurred on 23 and 24 August 2011 with redemptions of 798417 ounces and 876288 ounces, together 172 baskets or about 52 tonnes of gold. This coincides with the following reported Gold Forward Offered Rates (GOFO) found on the LBMA website at that time. The numbers are GOFO for 1,2,3,6 and 12 months:

19-Aug-11 0.40000 0.41600 0.42600 0.48800 0.51000

22-Aug-11 0.48250 0.43000 0.35000 0.25000 0.08750

23-Aug-11 0.40800 0.41600 0.42250 0.50000 0.52600

The term structure beyond one month was inverted on 22 August 2011, indicating that some bullion bank(s) frantically tried to borrow gold in the OTC market, gold that was needed within one to two months. They were willing to buy one-month forward and sell a longer forward at a discount. Recall that the GOFO rates reported on the LBMA website are not individual quotes that can be associated with a specific bullion bank, but rather the averages from their daily telephone survey of the major market makers. Also note that a few days later, these numbers were ‘corrected’ on the LBMA website.

A third example was again reported by Izabella Kaminska. On 10 August 2011, Société Générale quoted an inverted term structure:

Again, this coincides with losses of GLD inventory of 418373 ounces on 9 August 2011, 759559 ounces on 11 August 2011 and 408988 ounces on 12 August 2011, together 1.59 million ounces, 164 baskets or 49.3 tonnes. Since Société Générale is not an AP, apparently someone else took the gold out of GLD and lent it to them.

We have to concede that the published GLD inventory only records the aggregate daily changes. The fax from HSBC that Warren James at Screwtape Files discovered, shows redemptions of 759618 ounces for 16 August 2011. This must have been some intra-day movement that was compensated by even larger creations on the same day because the reported aggregate change of inventory for that day is positive. Apparently the inventory changes are such a good indicator that the trading strategy is still effective even if we work with daily aggregates only.

Interpretation

We arrive at the interpretation that large allocation requests by customers of a bullion bank sometimes force the bullion bank to take physical gold out of GLD. This is a buy signal that indicates a higher price of paper gold in the near future. Conversely, once the bullion bank has replenished its reserve of physical gold and shifts a part of this back into GLD, this forms a sell signal that indicates a less rapidly increasing price of paper gold in the near future.

FOFOA must have had this picture in mind when he called GLD the Central Bank of the Bullion Banks, i.e. a depository of additional reserves shared by those bullion banks that are at the same time APs.

It remains to understand why the paper price of gold rises during the period immediately following strong demand for physical gold.

Conservative Interpretation

A simple explanation is the following. Many large redemptions of GLD occur towards the end of a sell-off in the price of paper gold. There might be some sophisticated buyer(s) of physical gold who buy the dips and whose timing is excellent.

Notice that the buyer(s) purchase only about 5 to 50 tonnes of physical gold on the relevant days whereas about 2700 tonnes of paper gold are sold every trading day (total transaction volume of all sales, assuming 62.5 trading days per quarter) according to the Loco London Liquidity Survey published in August 2011. Although the physical purchase is tiny compared to the trading volume of paper gold, after this purchase the price of paper gold increases.

We might attribute this to the excellent timing of the large physical buyer whose activity we can sometimes spot by watching the inventory of GLD.

Speculative Interpretation

If you find this interpretation unsatisfactory and ask why should the paper price increase after the purchase of an amount of allocated gold that is small compared to the volume of paper gold traded, the only way out is more speculative.

What if somebody manages the price of paper gold in such a way as to control the flow of physical gold? The following chart shows the remarkably uniform increase in the dollar price of gold over the previous decade from 2002 to 2011. The black line is the regression line in the logarithmic diagram. It starts on 2 January 2002 at $266.60 and ends on 29 December 2011 at $1589.95 for an annual rate of increase of 19.56%. The blue and light blue bands are a factor of 1.118 and 1.25 away from the black line.

Does this chart look ‘managed’? Maybe…

How would one manage the price in such a way as to control the flow of physical gold? Let us make up some numbers in order to arrive at a toy model. There is a flow of new gold into the market from mining and recycling. This amounts to about 3000 tonnes per year. If a third of this amount goes through the London market, this amounts to about 4 tonnes per trading day (assuming 250 trading days per year).

In addition, there are some investors who sell allocated gold and some who purchase allocated gold. Let us be generous and assume that this trading volume of allocated gold is three times as big as the flow of new gold. This suggests a trading volume of 16 tonnes of physical gold per trading day in the London market which is tiny compared to the trading volume of paper gold (2700 tonnes per trading day). It is important to keep in mind that the inflow of new gold has an approximately constant weight per day.

It firstly seems plausible that allocation requests of about 5 to 50 tonnes are big enough in order to affect the reserve management of the bullion banks and thereby result in changes to the GLD inventory. It is also plausible that the management of the physical reserve that underlies the gold market is a rather delicate business because the paper trading volume is so huge compared to the physical volume.

Secondly, let us assume that the allocation requests by the buyers of physical gold involve an approximately constant sum of dollars per time. Investors or central banks who gradually switch from dollars into gold or who gradually diversify their foreign exchange reserves. We therefore have an inflow of physical gold that is steady in terms of weight per time, but an outflow that is steady in terms of dollars per time.

In order to manage the flow of physical gold, someone might therefore try to manage the dollar price of paper gold. Since the physical inflow is by weight, but the outflow by dollars, one might try to increase the paper price in response to an increased outflow of physical gold and try to lower the paper price whenever there are plenty of reserves. There you go. This is indeed consistent with what we see in our trading strategy: The price of paper gold increases in response to an outflow of physical gold.

Let us keep this speculation in mind as a second possible explanation of why the trading strategy works.

In light of this interpretation, it would be worthwhile watching the total inventory of GLD (the blue curve, right scale, in the very first diagram of this article). The inventory of GLD, the central bank of the bullion banks, should move in line with their total physical reserves. We see that the inventory peaked at 42.1 million ounces (1310 tonnes) in summer 2010, a level that has not been reached ever since. Even though the dollar price of gold rose further from $1200/ounce to $1900/ounce, the investors in GLD were not able to entice the APs to make additional inventory available.

Nevertheless, the present GLD inventory of still 40.84 million ounces (1270 tonnes) forms a considerable reserve of physical gold which the bullion banks can draw on in order to replenish their own reserves. Should the total inventory continue to decline, this would indicate increasing pressure on the physical reserves of the bullion banks. The financial media, however, would presumably tell you that investors are no longer interested in gold, that they sold their shares in GLD and that this was bearish for gold. Nothing would be further from the truth.

The SLV Inventory Strategy

The same trading strategy that we developed for gold, can also be applied to silver. We therefore watch the inventory of the iShares Silver Trust (SLV) whose inventory management is organized in the same way as that of GLD. Note that a share of SLV presently represents about 0.97 ounces of silver. One basket consists of 50000 shares, i.e. about 1.5 tonnes of silver presently worth $1.37 million (London silver fixing of $28.25/ounce on 29 May 2012).

The following histogram shows the distribution of the daily changes to the inventory of SLV.

Distribution of daily SLV inventory changes in millions of ounces from 1 January 2007 to 30 April 2012

The threshold for our trading strategy is an inventory change by at least 3.5 million ounces (about 108.9 tonnes worth $98.9 million). Apart from the choice of this threshold, the trading strategy is identical.

The following chart finally shows the performance of this strategy. The black curve (left scale) is the London Silver Fixing in U.S. Dollars. Again, buy and sell signals are indicated by green and red dots, respectively, and the light-blue shaded areas are the times during which the strategy is invested, i.e. about 25% of the time. During the invested periods, the silver price increases at an annualized rate of 28.7% whereas during the remaining times it increases only at an annualized rate of 11.6%. The blue curve (right scale) finally shows the total inventory of SLV.

Whereas in the case of GLD, basically any threshold beyond our 250000 ounces works, as long as it gives a sufficient number of signals at all, it is substantially more difficult to find efficient parameters for the strategy involving SLV and silver. Nevertheless, we do have an effective trading strategy, and so everything said about reserve management and GLD seems to apply to silver and SLV, too.

Comments

If you have comments, suggestions or corrections concerning this article, please comment here (comments are moderated, and it may take a while until I have time to check for new comments). FOFOA just opened a new thread GLD Talk Continued, and so for the further discussion, please take a look there.

so victor… there’s a lot here… i like your histograms!

“If it were just the arbitrage in response to the investors, why would the trading strategy work?”

how about mean reversion? if I understand your trading strategy, you’re BUYING big inventory declines, right? which would come via arbitrage after large periods of gold selling… when the selling is exhausted, gold rises.. and vice versa…

it’s not that GLD is driven by “Weak” hands, although maybe you could call it that if you want: it’s that GLD is EASY… and cheaper.. it’s much easier to buy GLD than it is to call around to a bunch of gold dealers, figure out who to trust, pay for shipping, charge $100k on your credit card, etc… store the gold at home, etc… this of course is why GLD has been so beneficial to the price of gold – it’s allowed the layman to “purchase” physical gold (indirectly, via the AP’s arbitrage mechanism, as you noted, of course)…. so, yes – there is a massive base of “GLD only” investors – people who will buy (or simply trade) GLD instead of bullion, and would never buy/trade bullion.

as for the arbitrage itself – it is indeed done for small amounts – and the transactions costs of creation/redemption are non-zero, but easily recouped in the size baskets that you’re talking about. That’s one reason why GLD has multiple sub-custodians: to make it easy to deliver gold without, as some ignorant goldbugs constantly wonder about the logistics – unloading trucks full of bullion every night. The bullion either doesn’t move (just the title does), or just moves across the hall or across the vault. That’s also why Sprott didn’t base his funds in London – he could have gotten the gold/silver in a matter of hours or days, and the ghost stories of shortages and delays (which are really just shipping logistics) wouldn’t have contributed to the the early 2011 bubble in the metals…

moving on: what makes you think that bullion bank would store inventory in the form of GLD shares? the entire point of a BB is that they can store the gold more efficiently (cheaper) than GLD can! so I don’t think that makes any sense. After all, one of the large holders (maybe it was Kyle Bass?) mentioned that he could store his gold cheaper than GLD in the size he held it…

finally, I don’t understand why you think that BBs would move inventory into GLD (Create) and then sell the shares – that gives them new price exposure that they didn’t previously have.

I thought you were getting at a topic that Izabella loves: create to lend – where BBs would take gold, deliver it to GLD creating new shares, and then LEND those shares to investors who will pay to short them! This does not create price exposure for the BB (although it does create credit risk) – and you’d need to look at historical GLD borrow rates to analyze it, which I think will prove very difficult data to get your hands on…

regarding your final paragraph about gold: you need to look at inventory and price together: inventory declines in the face of falling prices are probably bearish… inventory declines in the face of RISING prices are probably bullish – which I think was the point you were trying to “prove”

I am sorry, I have confused people by mixing up ‘increase’ and ‘decrease’ in the paragraph “The Trading Strategy In Detail” although I ought to know better because I programmed the thing. Please read it again. The red words are correct. Now it should all make sense.

I think it was Einhorn who said he could store it more cheaply (and who then did precisely that).

I like your suggestion about stock lending. That would be inventory financing in a fashion similar to the swap, just that your counterparty is the man on the street who who happens to own some GLD. The short interest gives you an upper bound on the volume of this position.

Why would the BB put their gold into GLD by selling their GLD shares if that creates new price exposure? Well, they can hedge the exposure in the paper gold market on margin and without putting down the full capital. That should be enough motivation.

I am not sure about your last point. The indicator works irrespective of whether the price is rising or not. Often, it is triggered towards the end of a price drop, but before the price starts to rise. Just take a loot at the previous week. The large trigger (about 15 tonnes) was on 22 May (Friday last week) with declining prices. This week it bounced, then tested the low a second time, and the actual price increase started only this Friday.

Best regards,

Victor

Victor asks,

“Does this chart (London gold fix ’02-’11) look managed?” It’s a very orderly rise, and one thing I will say about such an orderly, albeit very impressive rise, is that, from where I sit, such a rise does not support the view that gold, particularly physical gold, is in a mania.

eldorado,

the price of paper gold and the price of physical gold agree as long as the banks still accept your gold as a bank deposit and as long as they allocate your paper gold on request.

I agree with your comment about the mania. But then who is expecting a mania?

Victor

Many folks who are apt to comment about such things have long since characterized gold as being in a secular “bull market”. Secular bull markets, as I’m sure you are aware, invariably give way to a mania stage. My view, and that of FOFOA, who I know you are very well acquainted with, is that such a perspective misses the point entirely regarding gold.

Thank you Victor you’ve managed to make a complicated subject understandable

I have long wanted to buy GLD, but I’m worried after the late Bob Chapman stated that there isn’t enough gold to support the paper if everyone to take hold of physical gold.

With all ETFs, regardless of whether GLD or the Sprott fund, your main risk is that the ETF will be closed down and investors be paid off in cash precisely during those four weeks during which you rather needed to hold on to your gold. The same applies to all other financial products, say Goldmoney, at which you don’t own specific bars.

Victor

An excellent explanation Victor, which corresponds to my views on the way APs use GLD. While you touched on the subject I feel that short selling of GLD stock also comes into play here. Any AP who needs physical gold quickly could borrow GLD stock and use the borrowed stock to redeem actual metal to meet an demand for metal that is otherwise not available. The redemption is viewed by most market players as bearish which is actually beneficial to the holder of the short position. The short interest in both SLV and GLD has been quite high at times but I have not attempted to relate these peaks of short selling of GLD with redemptions.

Dear Apsyrtus,

if you have a time series of the short interest in GLD, somebody could take a look and check whether there is some correlation. The only data I have used is the official spreadsheet with the historical data, and so I don’t have anything useful to comment.

Well, what would be relevant is whether some investment funds actually lend shares. If the BB is an AP and a broker, they could borrow GLD shares as if they wanted to short them, but just keep the borrowed shares and take the gold out. I am not sure how useful this would be – perhaps it would keep the price of GLD from developing a premium. Do they want this? If there is a small premium, some other AP might put some gold in after all. So I am not so sure about this strategy.

Another question that interests me is whether the BBs swap GLD into the market (as in the example of inventory financing by swap). Since 2008, there have been exchange traded options on GLD, and the BBs could just sell GLD into the market and purchase a synthetic forward in the options market (buy a call and sell a put with the same strike at some future maturity – the put should be a bit out of the money in order to make the options behave European). Such positions are indeed there, but not very many. Perhaps three or four blocks of 15 tonnes equivalent. Probably the options are just not liquid enough to do this on a larger scale.

Victor

Unfortunately, timely or real time short interest data is hard to find. It’s one of the least transparent trading statistics which the DTTC and the market insiders keep well hidden. There seems to be plenty of GLD stock available to borrow, but I doubt that the APs would bother borrowing stock, as being alternatively short and long as part of their normal trading (while building up a parcel or distributing stock from a freshly issued parcel). As part of the process it seems possible that significant unreportable short positions could be generated.

Depending on the arbitrage and market movement APs could either cover the short directly on the stock market or alternatively by creating a full parcel and covering with new shares issued.

I have never believed that the GLD trustees “played games” with the redemption/creation process and that the number of shares actually issued always matched the actual physical gold in their control, but I don’t have the same confidence in the APs or the stock market. I have seen officially reported GLD short sales of well over 20 million shares (it was 17.33 million short at the latest report) which is close enough to 1.7 million ounces (52.8 tonnes) of gold traded as shares but isn’t actually covered by the GLD bars in the vault.

In effect the short sellers have “created” an extra 50+ tonnes of gold that can be redeemed by an AP simply because there is no way to distinguish between a share issued by the trust and backed by gold and a share borrowed into existence. Both can be redeemed for actual physical metal but the borrower has created that gold for a fraction of the value of the redeemed metal. Those shares are commonly borrowed from other margin accounts and the actual beneficial owner has no knowledge that his stock has been lent and it still retains its full value in his account and can be traded or redeemed just the same as any other share.

This is incorrect. Every share of GLD has an unambiguous owner. If an investment fund or an AP himself ‘lend’ shares, this ‘lending’ is a repurchase agreement. This means that the title to the shares is transferred for the duration of the ‘loan’, i.e. the ‘lender’ no longer owns these shares, but only has a promise that the ‘borrower’ will return (different) shares of GLD at some point in the future.

During the ‘loan’ period, only the ‘borrower’ can get their hands on the gold, but the ‘lender’ does not have title to the shares and cannot get to the gold.

Victor

PS: Note that Ted Butler keeps publishing false claims about the mechanics of short sales, and although people have explained it to him, he keeps repeating the nonsense.

Thanks for the correction.

Some years ago I had the misfortune of buying shares in a stock where far more shares had been sold than were ever issued by the company. The broker who I had brought the shares through would not allow me to sell or transfer the stock. I actually attempted to have certificates issued but it took years before they were delivered and the stock had been destroyed in the meantime. My experience on the mechanisms of short sales (especially naked short sales) is from experience not theory. I made formal complaints to the brokers, NASD, SEC and the company all without any satisfaction or compensation.

Getting back to GLD. From what you say it means that before an AP can sell shares in GLD he has to submit actual metal to the GLD trustee and get the shares issued first. To sell shares before he has them issued would entail him going short.

Alternatively the AP could borrow the equivalent of a parcel of shares from the market first, sell them and then replace the borrowed shares by the creation of new shares by the trustee in exchange for actual metal.

Which mechanism is the most common and how does the AP hedge during the process?

The AP can only sell shares that he already owns or that he has ‘borrowed’ (i.e. that he owns for the term of the ‘loan’).

Would you tell us which broker it was and shares of which company? From what you write I’d say this was plain fraud and your broker would have had to pay you the difference in price compared to the first sell instructions you gave them, wouldn’t you think?

In any case, the inventory movements of GLD do correlate with future prices, and this is an indication that the gold is there and that they merrily create and redeem, isn’t it? It’s surprisingly transparent.

Victor

Thanks Victor for such an elaborate explanation. Could you please explain specifically Ted Butler’s misunderstanding of the mechanics of short sale in the precious metals ETFs? Would you be referring to his article “A Hidden Silver Default?”? Thanks in advance!

Every share of GLD has a unique owner. If an AP wants to redeem, they need to own these shares.

If you “lend” shares to a short seller, in legal terms, this is a repurchase agreement. Title to these shares passes from you to the “borrower”, and you only have a promise that the borrower will return the same number of shares at some point in the future. As long as your shares are “on loan”, you don’t have title to these shares, but the borrower does. If he sells them into the market, the title passes on further to the buyer of these share. But the point is that as long as your shares are “on loan”, even if you are an AP, you cannot get to the gold because you don’t own these shares.

So there is never any ambiguous claim on shares of GLD. (Your broker might commit outright fraud and, although you send him a buy order, the broker might not buy shares for you, but rather hedge his exposure elsewhere). In a margin account, if you borrow against shares of GLD and these shares serve as collateral for the loan, you won’t have title – no surprise either). In general, people who hold GLD in margin accounts and who use the margin, may not have title to GLD. But then, someone else does. Every share has one and only one owner.

Some final technicality. GLD is in street name only. This means you cannot register certificates in your own name nor have paper certificates mailed to you. But if you hold your GLD outright (not on margin), your broker has to keep them in a segregated account, and you get all benefits of ownership from these shares, and they cannot be lent without your consent. (I am not a lawyer though!)

I don’t read Butler any more. Apologies for the rude response, but that has turned out to be a waste of time.

Victor

Thanks Victor for the clarification. Much appreciated.

Whoever reads this should also take a look here:

http://www.fofoa.blogspot.cz/2012/06/gld-talk-continued.html

…+ comments VtC left under the article.

Pingback: GLD Talk Continued [FOFOA] « Mktgeist blog

Victor,

Can you speculate on what effect the Saudi take down of the oil price has on this analysis?

IE, if the KSA is successful in driving oil down to $60 for 24 months & the relentless acquisition of physical metal by giants pushes the price over $2K, that gives an OGR of 33 or about double where we are now. Do the algorithms blow up at that point or does it ever get that far?

Milamber

Firstly, I think that reaching $60-$70/bbl is possible. Definitely if the speculation collapses, but (if SA and OPEC wants) then even for a longer period. Now you would need (paper) gold beyond $1800/oz to get the gold/oil ratio out of its 70-year trading range.

I am not sure the algorithms would fail at that point, but the oil exporters would certainly have an incentive to reconsider whether they really want to use the dollar.

Victor

Re does the gold price look managed?

It seems that important lows occur when GOFO rates are very low or negative, which, as you’ve shown in this post, also appear to occur with GLD redemptions. Low to negative GOFO points to two, seemingly contradictory things. Firstly it signals scarcity of physical metal. But it also says gold is in high demand as collateral for US dollar loans.

So the way i think about it is as follows:

During periods of tight liquidty the paper gold price just acts like the rest of the market – it sells off. A falling price attracts large buyers of physical. This sends GOFO down. So even though we have a falling paper price, you’re getting less liquidity in physical market…maybe because the financial turmoil encourage more people to request allocated.

If too much physical starts leaving the market – the whole paper money game and all the derivatives built on top of it – is over. The only way to attract physical back into the market (perhaps after taking what’s urgently needed via GLD) is to have the price shoot up.

What causes this i dont know. But from memory in Sept 99 and Nov 08 negative GOFO rates marked the absolute bottom of the corrections. From that point prices exploded upwards. Higher prices encourage supply. So physical comes back into the market in enough size to keep the game going. Hence the price is ‘managed’ higher.

But each year it takes a higher and higher gold price to convince enough people to part with their gold…hence this bull market has been so relentless.

I doubt i’ve thought this through enough but it seems like a plausable explanation.

cheers,

gc

As for GOFO, you can take a look at the very first article on my blog: Backwardation …

By term structure arbitrage, GOFO should agree with the nominal risk-free interest rate plus storage expenses. If this is not the case, there is either some counterparty risk expressed in the rate, or the arbitrage is not effective.

If you desperately need to borrow gold (and you are a bank), you would offer to make dollar loans that are collateralized with gold, i.e. basically a dollar for gold swap. If you are under pressure, you might have to offer a very low rate, perhaps negative. I don’t think there is any guarantee that GOFO is driven by physical gold alone – it may as well be paper. But paper gold is easy to create, and so I suppose what we are seeing is because of physical gold. Wes, you are right, GOFO turned negative at precisely the interesting occasions.

Victor

just read this at FOFOA’s latest post. It also seems to suggest that a falling paper price is coincident with disappearing physical…and firing up the price is a method to get the physical back.

cheers, gc

with quote…

‘And if these price rises in the gold market fail to manage the flow (demand) of physical as they have so far, we’ll likely see a 10% or larger GLD puke at some point. That would signify more than a 120 tonne allocation demand, a system-busting size. They might think they can rocket the price at that point and get it back, but more likely we’ll see more allocation requests coincident with a falling (paper) “gold” price as the longs dump their worthless “insurance” while wishing they had the real thing.’

Regarding GLD short interest, it’s reported every two weeks delayed a couple of weeks.

a)Most recent

05/15/2012 17 331 576

04/30/2012 17 896 537

04/13/2012 12 535 802

b) If we go back to August 2011, we see short interest build from 29/4/11 19.4m shares to a record 31.1m shares on 15/8/11 before falling back to 19.6m shares on 30/9/11

All consistent with sharp increases in prices squeezing out short positions.

The GLD short interest is meaningful… 1.7m ounces now (~50tonnes) and a peak of 3.1m ounces (~100tonnes) last August.

In other words, we know that GLD is easy to borrow in big amounts (all the short interest in GLD has to have borrowed GLD, and maybe bullion banks have borrowed additionally for themselves and redeemed to get hold of physical) – enough pension funds etc see lending GLD as just like lending any other stock..a little bit of fee income and no risk.

We don’t know either the total amount of GLD borrowed or how this compares to the trade volumes that go through on LBMA (at GOFO rates).

Maybe GLD borrow is bigger? (And how do the gold interest rates compare?)

Anyway, what we seem to have is:

Speculators borrow GLD and sell short/sell paper gold; paper gold price goes down (but bullion banks get extra requests to transfer from unallocated to allocated); bullion banks sell paper gold and buy GLD; bullion banks redeem GLD and get physical gold to meet allocation requests. This works fine on the basis that bullion banks can sell paper/buy GLD profitably (trigger waterfall declines in paper and sit on the bid in GLD perhaps?).

This ends when GLD stops being easy to borrow (or when selling paper doesn’t work but only stimulates fresh demand for allocated).

Please also take a look at Kid Dynamite’s blog for another coincidence involving GLD:

Did Eric Sprott Buy and Redeem GLD?

I don’t think Sprott bought GLD and then asked an AP to redeem it for him. If this had come out, it would have been just too embarrassing: in order to supply his own ETF, Sprott just purchased the competitor ETF and had it delivered. No way he would have risked this embarrassment.

So he probably asked a BB for the gold (people say it involved J.P. Morgan and RBC). Apparently, they took it out of GLD, and either shipped it across the Atlantic Ocean or swapped it with some other gold that was already located in New York. What an irony.

Victor

I chased down the typical costs to borrow GLD – seem around 0.10% p.a. …much cheaper than GOFO. I.e., a bullion bank neding physical would prefer to borrow GLD and redeem than borrow gold on LBMA

I think you should compare the borrowing costs of GLD shares with the Gold Lease Rate (GLR), i.e. LIBOR-GOFO rather than with GOFO. This is because you only borrow GLD shares, but you do not lend the other party dollars at the same time. GOFO is lending gold and borrowing dollars at the same time.

In any case, this figure is interesting. If you can borrow more than 2.5 million shares (threshold of the trading strategy) at this rate of 0.1% p.a., this is probably the cheapest way of borrowing gold. For a comparison, Kitco quotes a GLR of 0.5% for a 1-year term. (There is a difference though: your borrowing costs of GLD shares are probably subject to a recall by the lender at any time whereas the rate quoted by Kitco is fixed-term for the full year).

Why is it so much cheaper to borrow GLD rather than physical gold itself? Perhaps many investment funds have GLD, but view it only as a paper position, do not care about counterparty risk and are therefore happy to lend it out?

Victor

Sorry..I meant the implied gold interest rate from GOFO of course.

I think you are exactly right…GLD is considered by many pension fund type holders as just another security to be lent out to get fee income in. The loan will be collateralised (with some other of paper or cash) so is perceived to have no risk. Holders of GLD have no intention (or no capacity – was talking to a fund manager today who simply isn’t allowed to hold physical gold) to take delivery of physical. Only the bullion banks are playing across the two markets (LBMA and GLD).

Risk of recall is generally trivial… at least until the level of borrow gets to extreme levels (say 25% of all securities) and I doubt the first to have the securities recalled would be the bullion banks themselves (their clients come first I would think).

So cheap and easy borrow in very large amounts.

Tightness in GLD borrow (interest rate > GLR; GLR rising) would therefore be a very important signal that the game is close to over (and may well come before the final massive gold puke)

I agree, that’s all very plausible. Funny that in this scenario there are some who borrow stock not in order to sell it short, but rather in order to get to the gold.

Victor

GLD inventory peaked at just over 1279 tons. It last reported this number on the 6th of July, on a Friday. Inventory dropped on the 9th, the following Monday, then on 10th, 12th, and sixteenth this month. The cumulative reduction is now nearly 13 tons or just over 1%.

Lots of small vomiting makes a puke?

The inventory was 1281 tonnes during most of June after the puke of May 22 had almost been replenished. After this, you are right, we are now down to 1266 in several small steps. But for the trading strategy (both mine and Lance Lewis’) the criterion is the loss of inventory on a single day. So we didn’t have any further signal.

Morally speaking, you might still say that at the current low gold price, the ‘system’ keeps losing inventory, slowly but steadily.

Victor

Lost another 9.06 tons today, or 291,031oz. it satisfies your threshold of 250,000oz.

Yes. Since May 22, there has been no buy and no sell signal. July 19 was the fist buy signal since then. As of Friday, July 20, GLD has less inventory than on May 22.

Victor

Hello Victor.

I saw your quote on Twitter from Benoit Coeure re ‘the period during which sovereign debt was held as an international reserve is coming to an end’.

I have been scanning his recent speeches at the ECB website, but can’t find it. Would you be able to point me in the right direction to where you found it please?

Many thanks.

Gary.

Good question. I was unable to find the source myself. I hope I am right that it was Benoit Coeure. I am sure it was a speech by a member of the ECB gov council at some point during the summer of 2011. Someone at FOFOA must have posted that link. As soon as I have time, I’ll continue searching.

Victor

Good find on the Noyer quote, thanks.

Just for the record, the quote is here at FOFOA’s. And, yes, it was Noyer (BIS, Banque de France) and not Coeure as I thought.

Victor

As people keep asking me, here is the list of all GLD signals since I wrote the article:

22 May 2012: buy

19 July 2012: buy

17 August 2012: sell

14 September 2012: sell

21 September 2012: sell (new high of the total inventory: 1317 tonnes)

24 September 2012: sell (new high: 1326 tonnes)

26 September 2012: buy (h/t enough – now it’s getting interesting)

4 October 2012: sell (new high: 1333 tonnes)

3 January 2013: buy (inventory now 1340 tonnes after an intermediate high of 1353.35 tonnes)

20 February 2013: buy (loss of 20.77 tonnes which is more than 1% of the inventory and therefore a puke according to Lance Lewis)

21 February 2013: buy

22 February 2013: buy

25 February 2013: buy

27 February 2013: buy (loss of 12.04 tonnes or 0.95% – almost a puke according to Lance Lewis)

5 March 2013: buy (inventory now down more than 100 tonnes since 1 January 2013 to 1244.86 tonnes)

18 March 2013: buy (loss of 13.55 tonnes which is a puke according to Lance Lewis)

2 April 2013: buy

10 April 2013: buy (loss of 16.86 tonnes or 1.4% of inventory, a puke according to Lance Lewis)

12 April 2013: buy (loss of 22.86 tonnes or 1.93% of inventory, another puke)

16 April 2013: buy

17 April 2013: buy

19 April 2013: buy

22 April 2013: buy (loss of 18.35 tonnes or 1.63% of inventory, another puke)

21 May 2013: buy

25 June 2013: buy (loss of 16.23 tonnes or 1.65% of inventory, another puke)

8 July 2013: buy (loss of 15.03 tonnes or 1.56% of inventory, another puke)

22 October 2013: buy (loss of 10.51 tonnes or 1.19% of inventory, another puke)

16 December 2013: buy (loss of 8.70 tonnes or 1.02% of inventory, another puke, inventory now down to 818.9 tonnes)

23 December 2013: buy (loss of 8.40 tonnes or 1.03% of inventory, another puke)

17 January 2014: sell (gain of 7.49 tonnes or 0.95% of inventory, almost a reverse puke)

10 March 2014: sell (gain of 7.50 tonnes or 0.93% of inventory, almost a reverse puke)

16 April 2014: buy (loss of 8.39 tonnes or 1.04% of inventory, a puke)

27 May 2014: sell (gain of 8.39 tonnes or 1.08% of inventory, a reverse puke)

14 July 2014: sell (gain of 8.68 tonnes or 1.08% of inventory, a reverse puke)

19 September 2014: buy (loss of 7.73 tonnes or 0.99% of inventory, almost a regular puke, reaching a new of of inventory at 776.44 tonnes)

20 October 2014: buy (loss of 8.97 tonnes or 1.18% of inventory, a puke), new low of inventory at 751.96 tonnes.

23 December 2014: buy (loss of 11.65 tonnes or 1.61% of inventory, a puke), new low level of inventory at 712.90 tonnes.

15 January 2015: sell (gain of 9.56 tonnes or 1.35% of inventory, a reverse puke)

16 January 2015: sell (gain of 13.74 tonnes or 1.92% of inventory, a reverse puke)

20 January 2015: sell (gain of 11.35 tonnes or 1.55% of inventory, a reverse puke)

1 February 2015: sell (gain of 8.36 tonnes or 1.10% of inventory, a reverse puke)

2 March 2015: buy (loss of 7.76 tonnes or 1.01% of inventory, a puke)

8 May 2015: buy (loss of 10.75 tonnes or 1.45% of inventory, a puke)

17 July 2015: buy (loss of 11.63 tonnes or 1.64% of inventory, a puke), new low level of inventory at 696.25 tonnes

31 July 2015: buy (loss of 7.45t tonnes or 1.10% of inventory, a puke), new low level of inventory at 672.70 tonnes

5 November 2015: buy (loss of 8.34 tonnes or 1.23% of inventory, a puke).

2 December 2015: buy (loss of 15.78 tonnes or 2.41% of inventory, a puke), new low level of inventory at 639.02 tonnes

1 February 2016: sell (gain of 12.2 tonnes or 1.82% of inventory, a reverse puke)

11 February 2016: sell (gain of 13.98 tonnes or 1.99% of inventory, a reverse puke)

19 February 2016: sell (gain of 19.33 tonnes or 2.71% of inventory, a reverse puke)

22 February 2016: sell (gain of 19.33 tonnes or 2.64% of inventory, a reverse puke)

29 February 2016: sell (gain of 14.87 tonnes or 1.95% of inventory, a reverse puke)

1 March 2016: sell (gain of 8.93 tonnes or1.15% of inventory, a reverse puke), iventory now 786.2 tonnes, about 150 tonnes above a low in late 2015.

Victor

In the discussion in FOFOA’s GLD Talk Continued, one question was how to interpret the 2011 Loco London Liquidity Survey. The discussion was later continued in the comments section at FOFOA’s blog.

Pingback: About That Big Change To SLV's Silver Inventories - Kid Dynamite's World | Kid Dynamite's World

Victor

Thank you for the eye opening GLD post.

Related to GLD, could you assist in finding a reference for the top 500-1000 registered holders of the GLD etf?

I am afraid I don’t know anything better than using google, and that didn’t help.

You can search the 13F’s. thats how I try and keep up with who owns GLD (of size)

http://www.streetinsider.com/holdings.php?q=GLD

Goldman Sachs Asset Management, L.P. CMN 39,221,576 9.39% 13F

Mason Capital (CALL) ETF 26,298,300 6.29% 13F

GRUSS & CO INC GOLD SHS 25,378,111 6.07% 13F

Paulson & Co. (PCI) GOLD SHS 21,837,552 5.23% 13F

NORTHERN TRUST CORP COM 16,007,994 3.83% 13F

UBS AG GOLD SHS 12,308,062 2.95% 13F

JPMORGAN CHASE & CO COMMON 11,145,304 2.67% 13F

BARCLAYS PLC (CALL) OPT 10,050,100 2.40% 13F

SUN VALLEY GOLD LLC (CALL) GOLD SHS 7,998,000 1.91% 13F

CAPSTONE INVESTMENT ADVISORS, LLC

(PUT) COMMON 6,608,200 1.58% 13F

BLACKROCK ADVISORS LLC GOLD SHS 6,569,032 1.57% 13F

CITIGROUP INC (CALL) GOLD SHS 6,533,400 1.56% 13F

MORGAN STANLEY COM 6,335,830 1.52% 13F

CREDIT SUISSE AG/ GOLD SHS 6,093,952 1.46% 13F

ALLIANZ GLOBAL INVESTORS

OF AMERICA L P GOLD SHS 5,585,767 1.34% 13F

hth,

Milamber

Excellent analysis but I have a few questions, apologies if they’ve been answered somewhere else:

1) If physical arbitrage is normally unnecessary, why the continued rise in GLD inventory from late 2004 thru mid 2010 (longer term inventory and price graph: http://img546.imageshack.us/img546/3443/chartgolds.png ? Could it be because of the increased use of GLD as the Central Bank of Bullion banks, as GLD became accepted ?

2) Is there a way to track, or do you have an estimate of, the amount of GLD share liabilities of the APs vs the amt of GLD shares they own? Would that be the same as the GLD short interest? A statement in the FOFOA Open (Window?) forum that states,

“Do I need to report any new short sales of these shares? Nope. No one has short sold any shares.”

would seem to imply no to the latter question.

3) You made a strong case that at least large inventory redemptions are due to BB reserve management. But do you agree with the opening statement in the FOFOA post ?

“There seems to be a misunderstanding in the gold market that when you buy or sell shares of GLD you are putting pressure on the price of gold. That selling shares of GLD into the exchange is somehow analogous to selling physical into the marketplace. Or that buying shares of GLD is somehow, somewhere down the chain, removing physical gold from the marketplace.”

TIA

1) I am not saying that the usual arbitrage never plays a role. I am just suggesting that reserve management is a significant driver of GLD inventory. So for the time until mid 2009, we have two candidate processes for the inventory growth.

a) The BBs saw that GLD gained traction, and they decided to outsource a part of their reserves. Of course, they cannot stuff everything into GLD immediately. This would depress the price of GLD shares, and so they need to do it gradually.

b) Perhaps some investors urgently wanted GLD, but not other forms of gold, and so GLD occasionally traded at a premium to the spot price of gold. In this case, the arbitrageurs would have gone short GLD and long unallocated gold – this is the usual arbitrage. Now, if the arbitrageur decides to square this position “in the physical market”, and he will do this only if he is confident he can allocate sufficient gold, he will create baskets of GLD from his unallocated gold and use them to close his short position in GLD.

If the arbitrageur did not want to close the position “in the physical market”, he might just decide to wait. Since everyone knows the net asset value of GLD, even in the absence of any volume traded, people will quote “the right” price for GLD. So some time later, after the special buying pressure has abated, GLD will trade at its net asset value again. In this situation, the arbitrageur can buy back GLD and sell his spot unallocated.

It is worth noting that in (b), the decision to close the arbitrage position by creating baskets of GLD, is voluntary.

2) Very good question! There are two steps involved in a common short sale: (a) borrow shares from some lender; (b) sell these shares into the market. I think (but I am not 100% certain and cannot point you to the right small-print to confirm) that it is (b) that’s reportable. So if an AP urgently needs to borrow gold, they could find someone who lends them GLD shares (some passive investment fund, say) and just redeem. If I am right, then this transaction is not reportable.

Someone pointed to the reported short interest figures in the discussion above.

3) I agree about 50% with FOFOA. The explanation is as in 1(b) above. If someone urgently buys GLD, then GLD may trade at a premium to the spot price for a while. If an arbitrageur steps in, selling GLD and buying spot gold, the buying pressure is diverted from GLD into the spot market. On the other hand, even in absence of any volume traded, the price of GLD in relation to the spot price is always known. So once the buying pressure abates, the GLD share price will naturally move there.

In order to understand this argument, imagine that GLD has not traded for a week, and nobody remembers the last price. Now you want to offer your GLD shares for sale. You would take a look at its net asset value in relation to the spot price and place a corresponding limit sell order. No buying or selling pressure is needed to get the price of GLD shares there.

Victor

This week, we have another coincidence in which GOFO has turned negative (the following are the swap rates taken from the LBMA website for 1,2,3,6 and 12 months)

05-Jul-13 0.01500 0.03167 0.05167 0.09667 0.21833

08-Jul-13 -0.06500 -0.04333 -0.03000 0.03500 0.18167

09-Jul-13 -0.10600 -0.08400 -0.07000 -0.01000 0.13800

10-Jul-13 -0.11167 -0.08000 -0.05833 -0.00167 0.14000

and at the same time, GLD has been losing a substantial amount of inventory (15 tonnes on Monday, July 8, and another 7 tonnes on Tuesday).

Randy Strauss’ and FOFOA’s point of view that the bullion banks use GLD for active reserve management is strongly supported by the different behaviour of GLD inventory compared with SLV inventory:

Since December 28, 2012, the gold price has dropped by 24.5% from $1664/oz to $1256/oz while the silver price has dropped by 35% from $29.95/oz to $19.37/oz. That’s roughly comparable, but with silver hit more seriously than gold. The inventory of GLD and SLV has behaved rather differently though:

SLV inventory is almost unchanged, up 2% from 9925.6 tonnes to 10124.98 tonnes.

GLD inventory is down 30.5% from 1350.82 tonnes to 939.07 tonnes.

The arbitrage argument, i.e. that investors in gold and silver bid up or suppress the price of GLD or SLV shares relative to the spot price and then the APs respond by creating or redeeming baskets, can hardly explain the grossly different behaviour of gold and silver since the beginning of the year.

If the inventory changes in the case of GLD largely represent active reserve management, however, the development this year is understandable and indicates that large quantities of unallocated gold (“paper gold”) is being allocated, unallocated gold is being sold, or allocated gold is being purchased.

I was also asked to comment on Izabella Kaminska’s article on FT Alphaville. Note that she explicitly writes that she thinks negative GOFO is this time caused by spiking lease rates rather than by negative interest rates.

Victor